Moving forwards with the debate started in Glasgow (COP 26), one of the three round tables on day 2 was all about the buzz related to transitioning to a so-called hydrogen economy and the debate on whether or not it is a viable option especially for the global south hungry for cheaper fuel options. Will it save us or damage us depending on how much water is withdrawn for the purpose is part of that debate. Overall, it is seen that while it does have immediate positives the mantra that it reconverts back to water when it is combusted with oxygen to “provide additional water for a country” is just duckspeak. Additionally, there is always the issue that the production chain of hydrogen can come in a variety of colors such as gray, blue and green and even pink, yellow and turquoise. Only the green variety will be produced climate-neutrally.

With competing uses for water, well, the overall outcomes vis-à-vis human security in which both water security and energy security play a part may not be all that clear when the effort to secure the one may negatively impact the other. With the world facing significant water security issues with ACC (Anthropogenic Climate Change) causing droughts and desertification coupled with an ever increasing population of humans on the planet, the more water is withdrawn for purposes other than for natural consumption by animals, people and plants, the water problem may only be exacerbated by these moves.

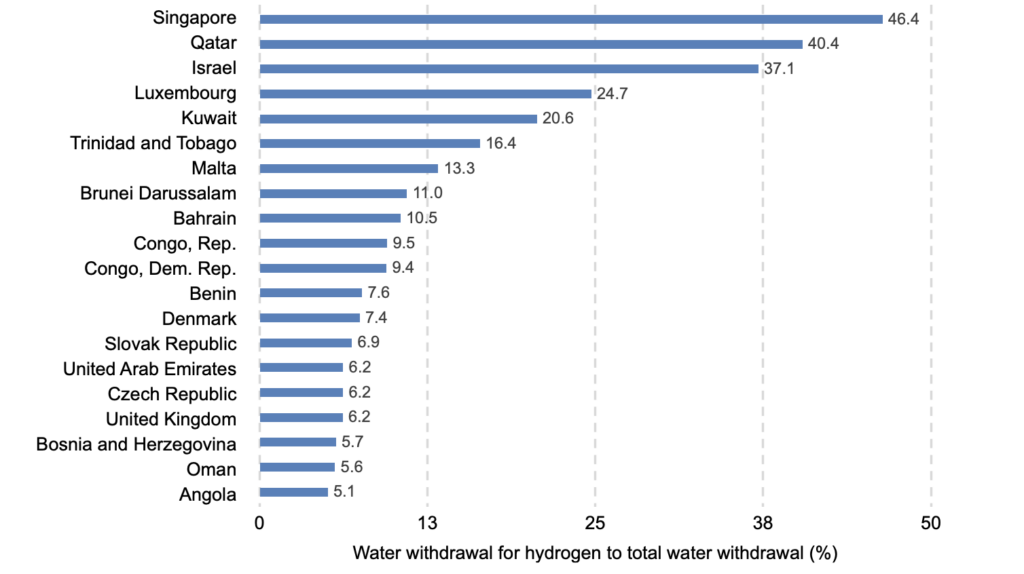

The countries with the highest water withdrawal for hydrogen to total water withdrawal: Source: World Bank and FAO

At present, 90 MT of hydrogen produced annually, just 0.5% is produced through renewable electricity while the rest comes from natural gas. 95% of current demand for hydrogen is in the Oil & Gas and Chemicals industries, to refine oil and produce ammonia or methanol.

However, ambitious plans have been put forward at the COP by various global north countries. Bart Kolodziejczyk, a research fellow at Monash University, Australia who studied the matter across 135 countries observes that only nine of the 135 countries studied would require an increase in their current freshwater withdrawal of over 10% to completely transition to hydrogen-based energy, whereas 62 countries would need to increase their freshwater withdrawal by less than 1%. There is a visible trend among the countries with a significant increase in water withdrawal to transition to hydrogen. These countries are either desert countries with little annual precipitation, such as Qatar, Israel, Kuwait or Bahrain, or small island states, such as Singapore, Trinidad and Tobago or Malta, which would also struggle due to limited freshwater reservoirs.

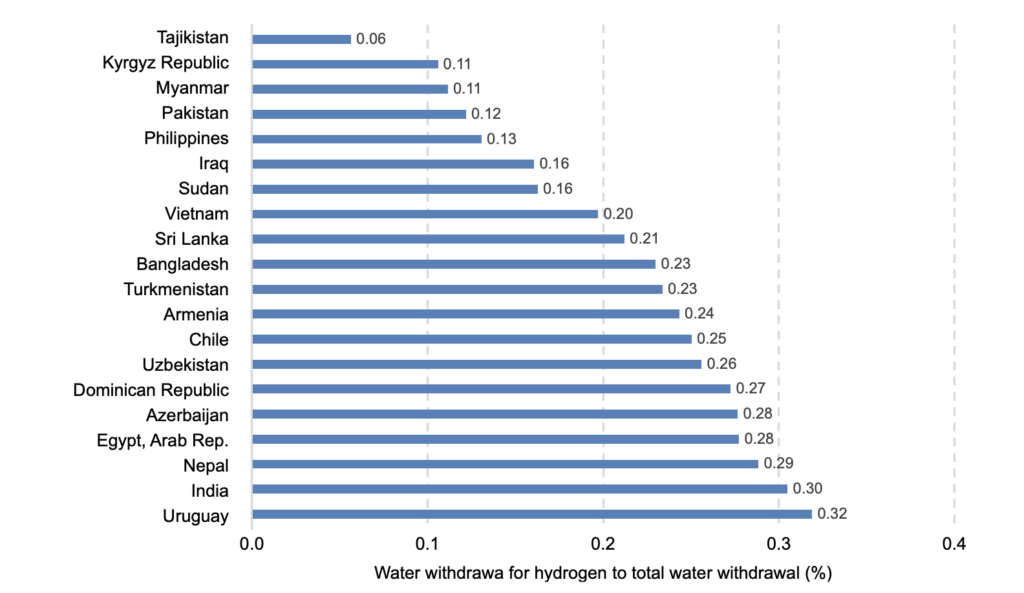

he countries with the lowest water withdrawal to meet energy demand in the form of hydrogen: Source World Bank and FAO

Singapore, which relies highly on neighbouring Malaysia for freshwater resources, tops the list. It would have to increase the water it uses to convert to hydrogen-based energy by about 46.4%. On the other hand, Tajikistan, being at the very bottom of the list, would require an increase of only 0.056%. The average value for all 135 countries is 3.3%.

Sri Lanka, in that respect, is seen in the lower segment of percent withdrawals of water for energy against total withdrawals. While we can certainly look at the option, we have enough alternative renewable sources (solar and wind) that are cheaper and do not compromise water volumes. A careful study of the future energy mix will be required for such countries as the global south and as things stand now, it is possible that there is no requirement for these to switch completely to a hydrogen society but rather, use that option within narrower demand side channels.