“We live in strange times indeed. Who would have thought that there can ever be an aid industry. Indeed, who can possibly link the word “aid” to the word “industry” without wondering if this is not a world gone mad. Well, it is a wacky world to be sure and one where the nonsensical becomes farcical and together become downright dangerous. As Doucouliagos and Paldam saw back in 2009, 40 years of aid resulted in zero growth and zero accumulation. Not 0.1% or 0.2% but a big round humpty. As aid recipients for many programs we do, we are more than a little ashamed because that assessment applies to us as well. The statements these two gents make are very revealing. First, it seems, aid promoters, implementers and other actors routinely lie through their teeth. Second, in order to validate those lies, they come up with a weird label called “best practices” which is another way of highlighting the few small gains and projecting them to be the norm instead of the exception. Additionally, when things go bad, they save their jobs with an equally weird term called “lessons learned”. Gentle people, I know very few best practices that have been replicated with the same good results and equally few lessons that aid practitioners have ever really learned. Third, and finally, Doucouliagos and Paldam indicate that the only resultants are glossy, learned reports with all the right lexicon, paraphrasing and conclusions that package in virtual beauty that which is ugly in reality. Let us consider all of this carefully. You see, unforgiving self-assessment and sober reflection are key components of any world that is sustainable”.(Arjuna Seneviratne, Speech at SEMA, “Outcome realities of an aid driven economy“)

The precursors of the movement formulate their ideology in the nineties

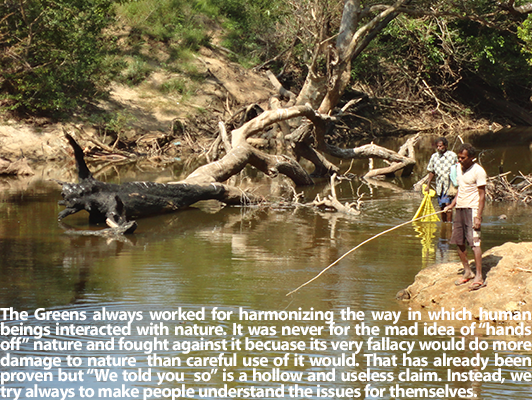

The people who eventually formed the Green Movement successfully engage with communities across the social spectrum from urban elites to adivasis, creating the trust that was sorely lacking in the work of environment protectionists whose approach was largely based on firefighting and reactive responses to real or imagined threats. This is the reason that when the idea of a movement was formed and finally executed, many community, district, province and national civil groups and organizations flocked to the umbrella.

The people who eventually formed the Green Movement successfully engage with communities across the social spectrum from urban elites to adivasis, creating the trust that was sorely lacking in the work of environment protectionists whose approach was largely based on firefighting and reactive responses to real or imagined threats. This is the reason that when the idea of a movement was formed and finally executed, many community, district, province and national civil groups and organizations flocked to the umbrella.

1998 – 2002: We lobby successfully for a proactive policy advocacy approach over a reactive grassroots strategy

Working on a largely voluntary basis with meager funds, the movement grows to successfully catch the attention of the Scandinavian countries who decide to support it over the long term. However, at that time, most of these external agencies considered grassroots responses to linear problems that could be addressed with limited funds as the only recourse to action. With the movement taking a diametrically opposite view to that of such assistance providers and local groups bent on simply attempting to move the legal machinery to find redress and relief for environmental issues, the movement is successful in showing everyone that grassroots activism and engagement was only relevant if those led to policy changes and from that time onwards, such organizations as the Development Fund of Norway not only commenced supporting policy advocacy in Sri Lanka but changed their approach worldwide to make that component a foundation for all of their community level work.

Working on a largely voluntary basis with meager funds, the movement grows to successfully catch the attention of the Scandinavian countries who decide to support it over the long term. However, at that time, most of these external agencies considered grassroots responses to linear problems that could be addressed with limited funds as the only recourse to action. With the movement taking a diametrically opposite view to that of such assistance providers and local groups bent on simply attempting to move the legal machinery to find redress and relief for environmental issues, the movement is successful in showing everyone that grassroots activism and engagement was only relevant if those led to policy changes and from that time onwards, such organizations as the Development Fund of Norway not only commenced supporting policy advocacy in Sri Lanka but changed their approach worldwide to make that component a foundation for all of their community level work.

Our report on sustainability for RIO+10 becomes a sensation 2002

Well now, we are very proud of this success. Our efforts, reflecting the deep sensitivity and oneness we had with the communities took the international debate to a new level where they finally had proof that without community ownership, nothing done was ever going to be successful. For many at the conference, the way in which that greens had unpacked the process of vesting ownership with the need-based users of our world as opposed to those that ravaged it in the name of greed and profit was, well, to put it mildly, “new thinking” which was quite um… strange to say the least because these were very smart people. Whatever the reason, our thinking became their thinking and colored the way in which some critical areas of debate went at that summit

Well now, we are very proud of this success. Our efforts, reflecting the deep sensitivity and oneness we had with the communities took the international debate to a new level where they finally had proof that without community ownership, nothing done was ever going to be successful. For many at the conference, the way in which that greens had unpacked the process of vesting ownership with the need-based users of our world as opposed to those that ravaged it in the name of greed and profit was, well, to put it mildly, “new thinking” which was quite um… strange to say the least because these were very smart people. Whatever the reason, our thinking became their thinking and colored the way in which some critical areas of debate went at that summit

2005-2007: Everyone reacted to the Asian tsunamis. We had a sustainable plan of community support

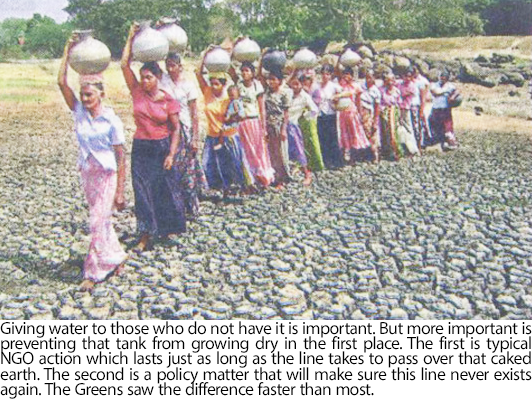

When they hit, we were hit. Like pretty much everyone else. Entire nations bowled themselves over each other to try to help as is the case when such tragedies hammer human societies. Most, well-meaning of course, quite a few self-serving *grin*, all, with one exception, with no plan. That exception was us. Our disaster mitigation program had been going on for a couple of years when this wall of water thumped into the country. Even with a program in place, the scale of the tragedy shook us. During the first two weeks, we did as the Bangladeshis do. Speedily restored the surface cosmetics that visually indicate “as was before, so it is now”. Then we really went to work, leveraging our in-place system to mitigate damage in our chosen areas for one purpose – durability of response. Earmarking the most damaged, environment sensitive and nationally critical geographies in Kalutara, Habaraduwa, Ambalantota and Tirukkovil, the GMSL rehabilitated entire villages. One, at Kalametiya became a showcase as the most successful post-tsunami rehabilitation program in Sri Lanka. The logic was simple – the GMSL did not built houses but homes. In that, it created the spaces, improved the environs, rehabilitated damaged fisheries livelihoods, improved infrastructure for water and electricity, rehabilitated surrounding ecosystems that has been damaged by the waves and finally, and critically, did something no one thought was possible – introduced land agriculture to fisher families. That last was so successful that it was not simply an alternative livelihood for them but rather, became a mainstream income source. By the time we moved out, the communities were in stronger and better shape than they were before the waves. We are quietly proud of our turnkey efforts. Yet, it was not all rosy. We messed up big time in some of our architecture, our reading of communities and even, at times, the quality of our own activists and their level of altruism and honesty. We managed to rectify and remedy most of the problems before they became impossible to handle but were aghast at the casual way in which many other agents of the do-good-brigade were going about the same things we were doing. Our reports on our own effort reflects that grit-teethed frustration, aimed, not only at the world but first, at our own selves, our human limitations and our human failings. .

2007-2009: We formulate the draft Disaster Management Act

What with the respect we got from the government for our work during the Tsunamis, we were given carte blanch by the then Minister of Disaster Management to go ahead and create a new disaster policy because the existing one was a top-heavy misery that was incapable of moving. Over two years, with support from Action Aid, we traversed the length and breadth of the country and finally, working with the Legal Draftsman’s department of the Government, created the draft policy in late June 2009. It was tabled to the Parliamentary Select Committee in mid-August after going through the usual channels. And then the war took over everything. The paper was put on the backburner and was never ever revisited. We still do not have a proper act because of that miss. Oh well, we succeeded in a sort of lopsided way in that everyone started polling the Greens before any policy moves but this particular one – well, to cut a long story short – it got away.

2005-2011: We are in the forefront of the Aid debate

And the 2005 Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness became! Sri Lanka played a key role in that but uh-oh! The whole thing, despite being created with best intentions on the part of OECD-DAC, um… left much to be desired. We tried to fill that gap. Working with EBON and the APRN network, as we prepared for the HLFs from Accra to Busan, the Greens were part of a core team that created the concept of Development Effectiveness over aid effectiveness. It was finally ratified at the Busan summit. We all pat ourselves quietly on the back for the effort the civil organizations from Asia, Africa, South America and Europe put in to get this done but we were sober in our assessment of its effectiveness in the longer run. Fast forward to 2021. Hindsight has proven that we were right to be reserved in our reaction. From then to now, we only need to look at the world to see that in many ways, our much-lauded work, despite best intentions, finally reduced to mere “busywork” that fell between the boards, somewhere between Busan and Covid.

2005 onward: We are the go-to guys for the government of Sri Lanka on almost all of the COPs

Whether we were in favor with the government or not, at all points during this long drawn and oft times frustrating international dialogue, the GMSL helped the government formulate its policy stances while also working on outside strategies with its greater network of international civil organizations. We shall always be proud of the fact that in many instances, we prevented the government from committing policy hara kiri while at others, we helped the debate on climate as part of the regional and global civil action networks. Yet, taking a step back from our years of engaging the climate process, we feel, as do most socio-environmental activists that there was more talk than action and that political posturing promoted disablers rather than create enablers for climate action. If asked, we would honestly say that our massive effort was akin to bashing our heads against a brick wall for all the good it did. Asked if we will continue, we would say yes because that is both our duty and our responsibility but we do not go into these debates with our eyes wide shut.

2013-2016: Our work in the Vanni is still much valued by our beneficiaries

The exercises to enhance agrarian livelihoods in these regions was supported by USAID. The program was comprehensive and looked at establishing and optimizing a loose amalgam between farmers, private sector organizations and civil agents that looked at the reality of conflict emergent communities and their needs – most importantly those related to children of the war era and how to manage the logistics of livelihoods while providing the best possible security and education for the young ones. While in some instances, due to lack of funds, certain outcomes were not possible, yet, the whole process provided the Vanni farmers with a new impetus to stick with or convert to organics while reducing much of the psychosocial issues our people living in the Vanni belt. We just wish that we had sufficient funds to actually complete our original program so overall, the effort was suboptimal.

2013-2015: Pidgeon Island glows after our teams brush its teeth and wash its face

Pidgeon Island MPA is one of the most picturesque and most visited attractions in the eastern region of the country. Anthropogenic activity takes its toll as we all know. We decided to clean up the mess and set the locals right on how to manage tourism sustainably. With help from the GEF-SGP we did exactly that, peeling back a lot of the grime and filth that has accumulated over the years. We are continuing to watch the situation over there. As we are all aware, unclean things take a lot of effort to clean up but clean things can be dirtied very quickly.

Pidgeon Island MPA is one of the most picturesque and most visited attractions in the eastern region of the country. Anthropogenic activity takes its toll as we all know. We decided to clean up the mess and set the locals right on how to manage tourism sustainably. With help from the GEF-SGP we did exactly that, peeling back a lot of the grime and filth that has accumulated over the years. We are continuing to watch the situation over there. As we are all aware, unclean things take a lot of effort to clean up but clean things can be dirtied very quickly.