Back in May 2023, I reported on the spike in ocean temperatures and issued our own warning to the people to get ready for a good old climate face-punch/kidney sock/kick to the nether human regions. I doubt that warning had any effect. In Sri Lanka, we try to stop things after those things have stopped hitting us and gone on to hit someone else. Perhaps, that is how the ego driven politically motivated South Asian region behaves. I do not really know. But? I can always cackle can I not??? hehehe!

El Niño (His full name is El Niño des Navidad – or “the child of Christmas” since most of these events occur in December) has visited us in Sri Lanka before. So too his sister La Niña. We got bopped by the boy in 2015-2016 when we recorded the highest rainfall ever in one year and the lowest ever the very next year. We got bopped by his sister with wacko rainfall in some areas and biscuit baking temperatures in others. Regardless of those, despite strong scientific foundations for ENSO (El Niño Southern Oscillation) predictions (especially for the tropical Pacific), of its global impacts it still a challenge since those impacts may be influenced by additional regional and local factors. So, let us be clear – while the onset factors can be predicted with some skill, the prediction of impact factors at a global level is still, at best, a work in progress.

Let us move carefully on these matters:

As a precursor to my argument, we had 2038.37 mm plus average rainfall in 2021, up from 1610.83 in 2020. This was during the transition from the girl to the boy. However, that rise did not mean that our still water bodies maintained strong reserves. The siltation of our reservoirs over the last three decades and the increase in global temperatures meant that a) reservoirs filled up quickly so sluices had to be opened to save the dams or b) the heat increased evaporation of whatever was left. So with that double whammy, water pressure remained significant over 2022-2023. So, let us be careful here folks. What we “see” may not be what we “have” in terms of impacts of such phenomena. Sure, some areas can fry such as the upper watershed because that area is drier than a desert these days but other areas are getting so much water that the net water falling on Sri Lanka might actually be positive although I have not seen any data on this yet. This goes to show the complexity of water dynamics and the difficulty of managing them when the influencing factors (such as siltation, watershed damage, cascading dams etc.) and multiplying factors (such as climate change, climate events) play out over a given terrain simultaneously.

Fires, floods, falls – the imact of ENSO events in Sri Lanka are a challenge to predict

ALL of this is serious. So serious that we cannot deal with it through casual inquiry or politically motivated surface reads. So serious that we need to look at the science very carefully.

Let us go to the science and then, let us deal with what is on our plate based on that science.

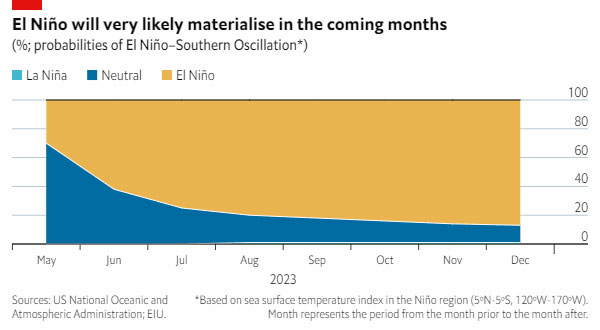

Source: Economic Intelligence

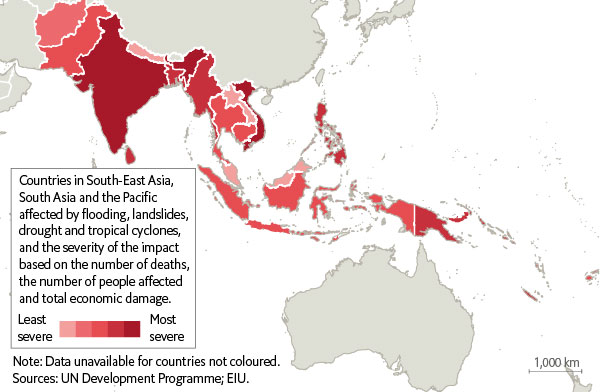

We must have a plan to respond to what scientists have already said would be ever increasing global temperatures (the last eight years have been the hottest on record ever despite the cooling effect of a particularly stubborn La Niña that extended across 3 years) and their impact in terms of either floods or droughts and such phenomena as El Niño which Economic Intelligence (EIU) predicts will probably materialize in the later part of the year as seen on left.

Let us look at a) the basic climate science related to ENSO scenarios (the actual science, the modeling mechanisms and the various indices that scientists use are quite complex and not of critical importance to this blog piece although I will inline links to a few papers and data resources for those interested), b) the economic impact and c) the social import of El Niño from both global and local perspectives.

The basic science:

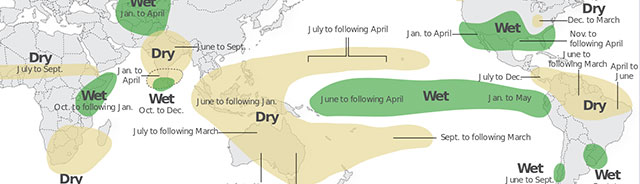

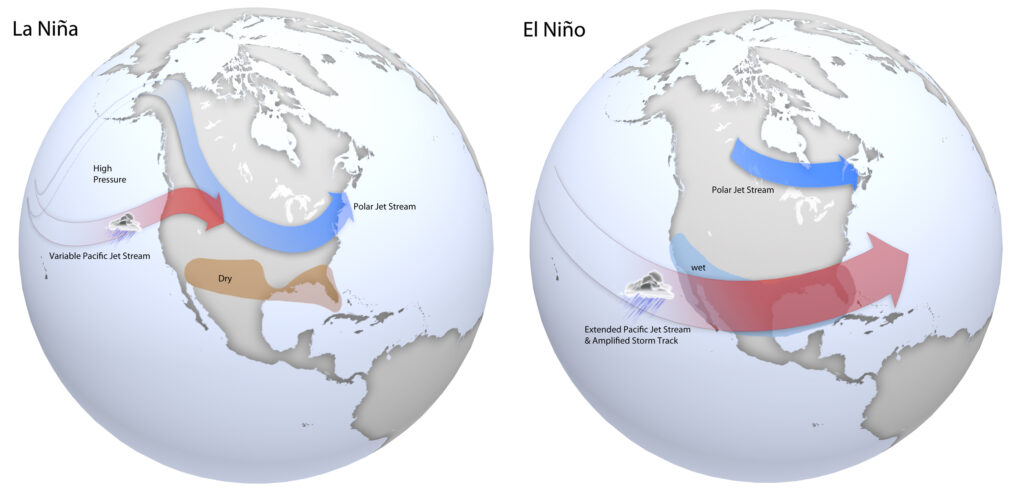

I will try to make this as brief and easy as possible for those who are fresh into these things. As mentioned before, some precursors of the impending climate event were present in April-May 2023 prompting the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) to warn of a high possibility of a full-fledged El Niño event developing later in the year. While the phenomenon occurs due to unusual warming of surface waters in the eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean its impact is global. This is because they are what are known as teleconnections which refers to the causal connection/correlation of meteorological or environment phenomena that occur a long distance apart. So, even though some met or environment event occurs in one part of the world, its impact is wide reaching and far spreading.

Both El Niño and La Niña are part of a recurring climate pattern involving changes to water temperature in the eastern tropical (equatorial) Pacific Ocean known as (already munitioned before) the El Niño Southern Oscillation or ENSO. While El Niño (Warmer Sea Surface Temperatures or SSTs), and La Niña (Cooler SSTs) are the extremes of ENSO, there is also an ENSO-neutral region in the tropical Pacific with average SSTs. Teleconnections such as ENSO, combined with the Indian teleconnection known as the Indian Ocean Dipole or IOD (this is the temperature differential between the western pole of the Arabian Sea and the eastern pole of the Eastern Indian Ocean (EIO) can impact precipitation in South Asia significantly with some areas becoming drier than usual while others become wetter or grossly unstable. These have impacts on economies that are dependent to some significant extent on agriculture and hydropower.

The Sri Lankan context in terms of the science:

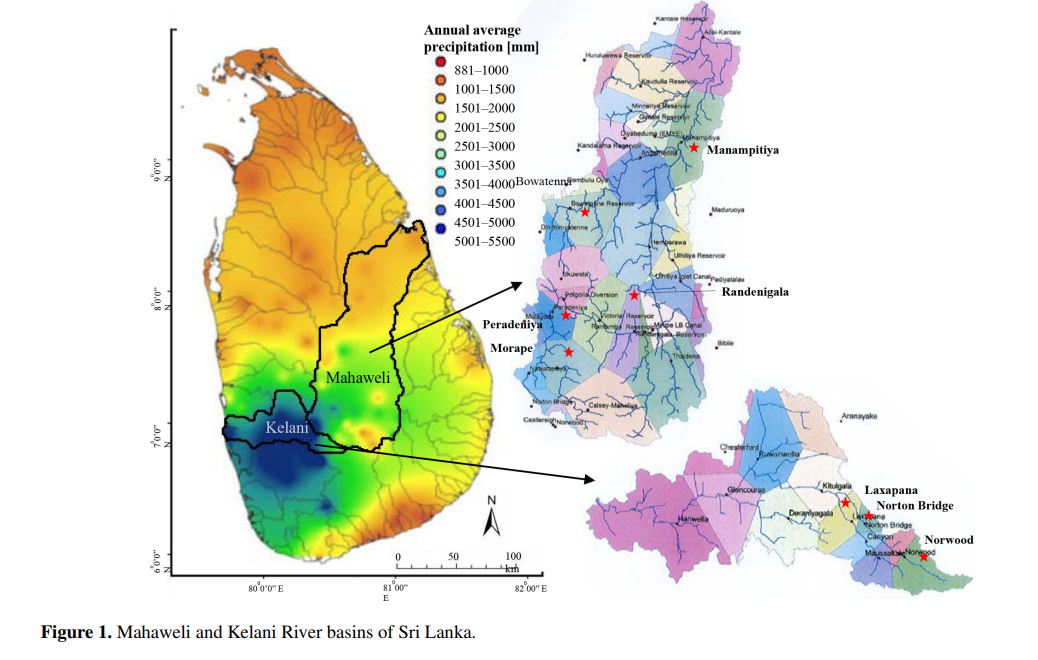

Deep analysis of the impacts of these phenomena with respect to Sri Lanka was done in 2019 along the Mahaweli Basin and the Kelani Basin (two critical hydrometeorological areas for irrigation and hydropower) by Thushara De Silva and George M. Hornberger. They report that results from the various models used were not very accurate; however, the patterns recognized provide useful input to water resource managers as they plan for adaptation of agriculture and mitigation of energy sectors in response to climate variability.

The two critical watersheds of Sri Lanka and average precipitation from 1950-2013 – Source De Silva and Hornberger

I shall desist from an analysis of their findings since the science is complex but nevertheless, it is important to note that good work has been done in Sri Lanka to identify trends related to teleconnections such as ENSO and IOD.

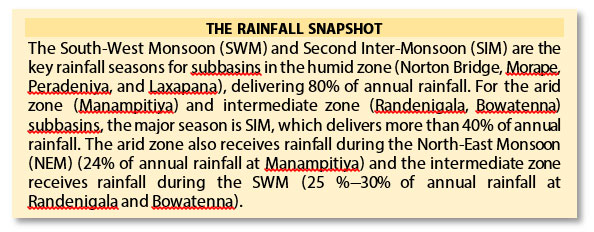

Suffice to say that their findings match with those of other investigators with higher correlation of rainfall anomalies to the Multivariate Enso Index or MEI. Analyzing data on the two above mentioned river basins, despite difficulties in efficacy of predictive models, th ey do state that in the spatially diverse Mahaweli and Kelani river basins, Climate teleconnection indices are related to rainfall anomalies observed during the two main growing seasons, Yala and Maha. During an El Niño event, the Maha rainfall (Second Inter Monsoon – SIM and North-East Monsoon – NEM) increases during the first three months and decreases during the last three months while during the Yala season, La Niña enhances effects during the South-Western Monsoon – SWM while during El Niño events, SWM rainfall is reduced. They also found that El Niño’s impact on the SWM is not as significant as its impact on the NEM but that there is a correlation between the teleconnection indices of MEI and IOD for SWM rainfall with a higher possibility of drought during the Yala Season but that no drought at all is probably when both the MEI and IOD are negative.

ey do state that in the spatially diverse Mahaweli and Kelani river basins, Climate teleconnection indices are related to rainfall anomalies observed during the two main growing seasons, Yala and Maha. During an El Niño event, the Maha rainfall (Second Inter Monsoon – SIM and North-East Monsoon – NEM) increases during the first three months and decreases during the last three months while during the Yala season, La Niña enhances effects during the South-Western Monsoon – SWM while during El Niño events, SWM rainfall is reduced. They also found that El Niño’s impact on the SWM is not as significant as its impact on the NEM but that there is a correlation between the teleconnection indices of MEI and IOD for SWM rainfall with a higher possibility of drought during the Yala Season but that no drought at all is probably when both the MEI and IOD are negative.

It is important then to note that the science gives us at least a general idea of what to expect in terms of the planning irrigation and hydropower strategies as we move into a significantly harsher short-term climate future.

The relevance or lack thereof of citizen science:

I am a great fan of citizen science but in this case, their predictive power is grossly reduced because the phenomena we are discussing are teleconnections whose unpredictability is augmented by global climate volatility. Citizen science works fantastically well under stable climate conditions and strong communities which are both lacking in this context and therefore, in my personal assessment of citizens knowledge of rapid fluxing climate events – well – sad to say – they know very little because their science is driven by long term assessment based on fairly stable parameters and they have no technique to say… measure long term precipitation at key points such as say Manampitiya (SIM/NEM) and Norton Bridge (SWM) in the Anthropocene (assuming commencement of this period in 1964) because the knowledge is transferred from generation to generation and over the last two generations, each new generation thought there was no value to that knowledge so intergenerational temporal predictive information got lost rather quickly. Now, a man who has lived 20 years in a hill station will be able to talk about what happened in the last 20 years but not what happened in the continuum of the last 60 years. So he will say … “the mist had disappeared over 20 years” but if asked why? He won’t know. If WE tell them… oh it’s because of climate change, ocean temperature rises, young Niño or young Niña or whatever, first, we may well be talking through our hats and second, we would only succeed in confusing and confounding the poor man. Speaking and listening to them over the last three years, I’ve had to come to the sad conclusion that they are not able to rely on their traditional science in this case and are looking everywhere but at themselves for solutions. Additionally, I’ve also found that many citizen scientists also have a fatal flaw in thinking/speaking/predicting about the reasons and the solutions to problems with such volatile systems casually and then slipping quietly away when their take is seen to be nonsense. This stuff is complicated. This means taking the utmost care in formulating responses. It cannot be de-complicated just because we wish it. So, in this specific case, unfortunately, I would not put too much trust in citizen science.

The economic impact on Sri Lanka:

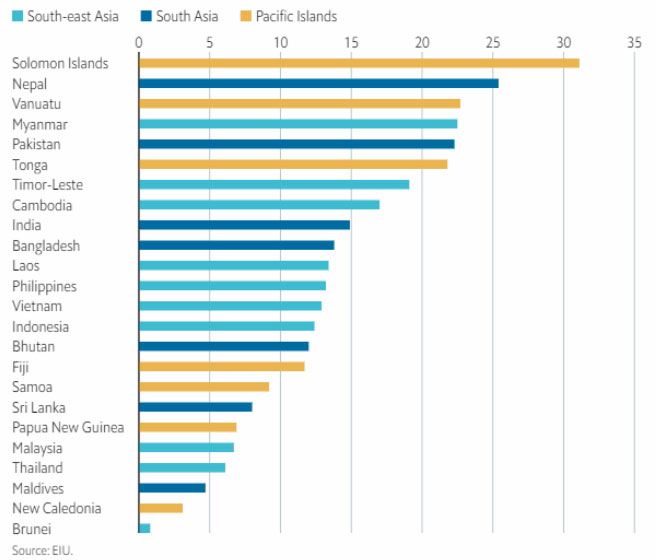

Figure2: Asian countries most impacted by last el Niño event 2015-2016

When asking ourselves the question on how severe the economic disruptions in Asia will be due to ENSO-IOD teleconnections, we must look at how exposed a country is to economic activity that is vulnerable to climate events. That means those countries whose economic output is based to a significant extent on agriculture and hydropower. Looking at the last strong El Niño event in 2015-2016, the diagram shows that Sri Lanka is just below India and Vietnam in those countries most victimized by the phenomenon. Economic Intelligence (EIU) stating something commonly known, has Sri Lanka somewhere in the middle of markets in South and South Asia that are developing, emerging or in states of financial flux. It expects both small and large scale farming and fishing to be significantly impacted by the phenomenon with high probabilities of poor/lost harvests, increase food inflation and hit rural communities very hard. Additionally, they predict that warmer weather will increase power demands while simultaneously putting pressure on hydropower stations due to possibly lower precipitation during specific periods with other negative influencers increasing that pressure as mentioned above.

As the Green Movement of Sri Lanka Inc. (GMSL) has often stated, not only in

Figure 3: Agriculture as a percentage of GDP in South and East Asia

Sri Lanka but in South Asia in general, lack of policy coherence, policy consistency, knowledge and awareness of the nuances of climate phenomena among lawmakers and the recalcitrance to factor climate into mainstream development strategy has resulted in poor administrative coordination between line agencies, weak governance and high levels of corruption. When ill-informed / ill-planned and environment devastating development projects are added on, the compound effect creates massive challenges to responding positively to climate events caused by ENSO-IOD teleconnections.

In that respect, while subject to review and recalibration based on local realities within micro-geographies, EIUs prediction for Sri Lanka in contrast to other countries in the region is particularly ominous: “The outlook for Sri Lanka, by contrast, is dimmer. Sri Lanka is particularly vulnerable to El Niño as a result of flooding: during the country’s last El Niño event in 2016, higher rainfall both depressed tea production and increased local incidence of dengue fever. Rising dengue cases—at already more than 31,000 by early 2023—suggest that a severe El Niño may further worsen the situation. Sri Lanka’s ongoing political and economic turmoil, however, will prevent a coordinated government plan to respond to a more severe El Niño, suggesting deeper economic shocks than our current assumptions”.

Is Sri Lanka prepared for climate shocks?

Short answer: No. Long answer: No. This is a terrible situation. Granted, most of Asia is also equally unprepared but that is small comfort for a country already hammered by its worst socioeconomic meltdown in history. Our disaster management policy has still to be ratified (and in its current form it is a mini-disaster in itself). We have no real plans in place for preparing the citizenry to adapt to long term climate challenges (agriculture) and mitigate them (energy). We have 46 agro-climatic zones that are dizzyingly interlaced with each other but just 40 agro-met stations across the country. The hydrometeorology of the upper watershed is (as far as I am aware) not mapped out comprehensively. Our responses to quick onset events (floods, landslides etc.) at the state level is so awful that in most cases it is the citizens who have to pitch in to help out. We have no idea about how to manage slow onset events (droughts, sea level rise, salinization of aquifers etc.). In short, as a nation, we are out at sea when it comes to climate response.

Most damningly, Sri Lanka’s policy makers either do not know the science or ignored the science. It also does not (at the very least) attempt to learn from good work done elsewhere choosing instead to bumble around in confused alarm with little or no idea of the surrounds. In the manner of men who has taken a series of serious hits to the head, they stumble here and tumble there, making policies, plans and predictions for a specific region in the country based on a wild combination of surface reads / political reads, rules-of-thumb, smatters of terrain geophysics spiced up a bit with dits and dots of climate science that will be lucky to hit the right galaxy leave aside the target terrain.

This must change now. It must be done through transdisciplinary approaches with a few non-negotiable policy decisions regarding watershed management, soil and silt management, terrain damaging business practices, fire control etc. through a whole-of-nation effort. If we succeed, we have done the best within our control to secure water both in terms of precipitation as well as availability. It will also help us become more resilient to things we cannot control that affect water – such as ENSO-IOD events.